The Times (UK, 2014)

At the scene of the crime: out after dark with the real Nightcrawlers

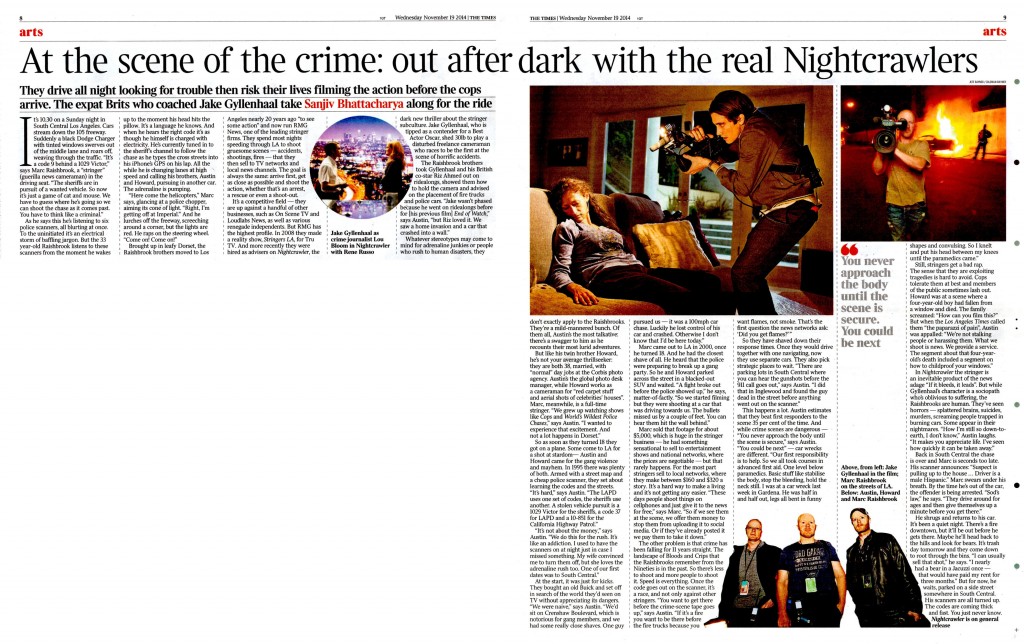

They drive all night looking for trouble then risk their lives filming the action before the cops arrive. The expat Brits who coached Jake Gyllenhaal take SanJiv Bhattacharya along for the ride

It’s 10.30 on a Sunday night in South Central Los Angeles. Cars stream down the 105 freeway. Suddenly a black Dodge Charger with tinted windows swerves out of the middle lane and roars off, weaving through the traffic. “It’s a code 9 behind a 1029 Victor,” says Marc Raishbrook, a “stringer” (guerilla news cameraman) in the driving seat. “The sheriffs are in pursuit of a wanted vehicle. So now it’s just a game of cat and mouse. We have to guess where he’s going so we can shoot the chase as it comes past. You have to think like a criminal.”

As he says this he’s listening to six police scanners, all blurting at once. To the uninitiated it’s an electrical storm of baffling jargon. But the 33 year-old Raishbrook listens to these scanners from the moment he wakes up to the moment his head hits the pillow. It’s a language he knows. And when he hears the right code it’s as though he himself is charged with electricity. He’s currently tuned in to the sheriff’s channel to follow the chase as he types the cross streets into his iPhone’s GPS on his lap. All the while he is changing lanes at high speed and calling his brothers, Austin and Howard, pursuing in another car. The adrenaline is pumping.

“Here come the helicopters,” Marc says, glancing at a police chopper, aiming its cone of light. “Right, I’m getting off at Imperial.” And he lurches off the freeway, screeching around a corner, but the lights are red. He raps on the steering wheel. “Come on! Come on!” Brought up in leafy Dorset, the Raishbrook brothers moved to Los Angeles nearly 20 years ago “to see some action” and now run RMG News, one of the leading stringer firms. They spend most nights speeding through LA to shoot gruesome scenes — accidents, shootings, fires — that they then sell to TV networks and local news channels. The goal is always the same: arrive first, get as close as possible and shoot the action, whether that’s an arrest, a rescue or even a shoot-out.

It’s a competitive field — they are up against a handful of other businesses, such as On Scene TV and Loudlabs News, as well as various renegade independents. But RMG has the highest profile. In 2008 they made a reality show, Stringers LA, for Tru TV. And more recently they were hired as advisers on Nightcrawler, the dark new thriller about the stringer subculture. Jake Gyllenhaal, who is tipped as a contender for a Best Actor Oscar, shed 30lb to play a disturbed freelance cameraman who races to be the first at the scene of horrific accidents.

The Raishbrook brothers took Gyllenhaal and his British co-star Riz Ahmed out on ridealongs, showed them how to hold the camera and advised on the placement of fire trucks and police cars. “Jake wasn’t phased because he went on ridealongs before for [his previous film] End of Watch,” says Austin, “but Riz loved it. We saw a home invasion and a car that crashed into a wall.”

Whatever stereotypes may come to mind for adrenaline junkies or people who rush to human disasters, they don’t exactly apply to the Raishbrooks. They’re a mild-mannered bunch. Of them all, Austin’s the most talkative: there’s a swagger to him as he recounts their most lurid adventures.

But like his twin brother Howard, he’s not your average thrillseeker: they are both 38, married, with “normal” day jobs at the Corbis photo agency. Austin’s the global photo desk manager, while Howard works as a cameraman for “red carpet stuff and aerial shots of celebrities’ houses”. Marc, meanwhile, is a full-time stringer. “We grew up watching shows like Cops and World’s Wildest Police Chases,” says Austin. “I wanted to experience that excitement. And not a lot happens in Dorset.”

So as soon as they turned 18 they got on a plane. Some come to LA for a shot at stardom— Austin and Howard came for the gang violence and mayhem. In 1995 there was plenty of both. Armed with a street map and a cheap police scanner, they set about learning the codes and the streets. “It’s hard,” says Austin. “The LAPD uses one set of codes, the sheriffs use another. A stolen vehicle pursuit is a 1029 Victor for the sheriffs, a code 37 for LAPD and a 10-851 for the California Highway Patrol.”

“It’s not about the money,” says Austin. “We do this for the rush. It’s like an addiction. I used to have the scanners on at night just in case I missed something. My wife convinced me to turn them off, but she loves the adrenaline rush too. One of our first dates was to South Central.”

At the start, it was just for kicks.

They bought an old Buick and set off in search of the world they’d seen on TV without appreciating its dangers. “We were naive,” says Austin. “We’d sit on Crenshaw Boulevard, which is notorious for gang members, and we had some really close shaves. One guy pursued us — it was a 100mph car chase. Luckily he lost control of his car and crashed. Otherwise I don’t know that I’d be here today.”

Marc came out to LA in 2000, once he turned 18. And he had the closest shave of all. He heard that the police were preparing to break up a gang party. So he and Howard parked across the street in a blacked-out SUV and waited. “A fight broke out before the police showed up,” he says, matter-of-factly. “So we started filming but they were shooting at a car that was driving towards us. The bullets missed us by a couple of feet. You can hear them hit the wall behind.”

Marc sold that footage for about $5,000, which is huge in the stringer business — he had something sensational to sell to entertainment shows and national networks, where the prices are negotiable — but that rarely happens. For the most part stringers sell to local networks, where they make between $160 and $320 a story. It’s a hard way to make a living and it’s not getting any easier. “These days people shoot things on cellphones and just give it to the news for free,” says Marc. “So if we see them at the scene, we offer them money to stop them from uploading it to social media. Or if they’ve already posted it we pay them to take it down.”

The other problem is that crime has been falling for 11 years straight. The landscape of Bloods and Crips that the Raishbrooks remember from the Nineties is in the past. So there’s less to shoot and more people to shoot it. Speed is everything. Once the code goes out on the scanner, it’s a race, and not only against other stringers. “You want to get there before the crime-scene tape goes up,” says Austin. “If it’s a fire you want to be there before the fire trucks because you want flames, not smoke. That’s the first question the news networks ask: ‘Did you get flames?’ ” So they have shaved down their response times. Once they would drive together with one navigating, now they use separate cars. They also pick strategic places to wait. “There are parking lots in South Central where you can hear the gunshots before the 911 call goes out,” says Austin. “I did that in Inglewood and found the guy dead in the street before anything went out on the scanner.”

This happens a lot. Austin estimates that they beat first responders to the scene 35 per cent of the time. And while crime scenes are dangerous — “You never approach the body until the scene is secure,” says Austin. “You could be next” — car wrecks are different. “Our first responsibility is to help. So we all took courses in advanced first aid. One level below paramedics. Basic stuff like stabilise the body, stop the bleeding, hold the neck still. I was at a car wreck last week in Gardena. He was half in and half out, legs all bent in funny shapes and convulsing. So I knelt and put his head between my knees until the paramedics came.”

Still, stringers get a bad rap. The sense that they are exploiting tragedies is hard to avoid. Cops tolerate them at best and members of the public sometimes lash out. Howard was at a scene where a four-year-old boy had fallen from a window and died. The family screamed: “How can you film this?” But when the Los Angeles Times called them “the paparazzi of pain”, Austin was appalled: “We’re not stalking people or harassing them. What we shoot is news. We provide a service. The segment about that four-yearold’s death included a segment on how to childproof your windows.”

In Nightcrawler the stringer is an inevitable product of the news adage “If it bleeds, it leads”. But while Gyllenhaal’s character is a sociopath who’s oblivious to suffering, the Raishbrooks are human. They’ve seen horrors — splattered brains, suicides, murders, screaming people trapped in burning cars. Some appear in their nightmares. “How I’m still so down-toearth, I don’t know,” Austin laughs. “It makes you appreciate life. I’ve seen how quickly it can be taken away.”

Back in South Central the chase is over and Marc is seconds too late. His scanner announces: “Suspect is pulling up to the house … Driver is a male Hispanic.” Marc swears under his breath. By the time he’s out of the car, the offender is being arrested. “Sod’s law,” he says. “They drive around for ages and then give themselves up a minute before you get there.”

He shrugs and returns to his car. It’s been a quiet night. There’s a fire downtown, but it’ll be out before he gets there. Maybe he’ll head back to the hills and look for bears. It’s trash day tomorrow and they come down to root through the bins. “I can usually sell that shot,” he says. “I nearly had a bear in a Jacuzzi once — that would have paid my rent for three months.” But for now, he waits, parked on a side street somewhere in South Central. His scanners are all turned up. The codes are coming thick and fast. You just never know.